This article was originally published by The Phoenix Times.

The state senator is in a tough race for a spot on the Phoenix City Council. She’ll face hurdles even if she wins.

By TJ L’Heureux

October 21, 2024

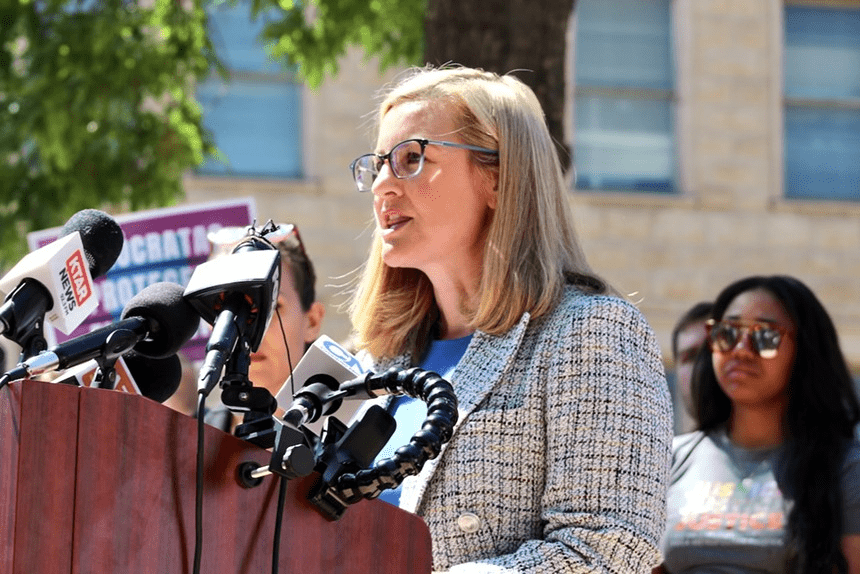

State Sen. Anna Hernandez wants to push Phoenix in a more progressive direction, but first she’ll have to win a seat on the city council. Illustration by Eric Torres

Editor’s note: A previous version of this story misstated District 7 candidate Michael Nowakowski’s history. He has a history of corruption allegations, not necessarily a history of corruption. We regret the error.

State Sen. Anna Hernandez didn’t expect to become an elected official. Well into a career selling mortgages in corporate America, the Phoenix native was doing well for herself. Then in 2019, Phoenix police shot and killed her brother, Alejandro, while he was experiencing a mental health crisis.

She started asking questions about Alejandro’s killing. The death certificate from a funeral home showed Alejandro had multiple gunshot wounds, contradicting the police narrative. “When we talked to the detective that day they killed him,” Hernandez said, “they had said my brother was only shot one time.

“That was the moment I really started getting involved,” Hernandez said of Alejandro’s death. A tattoo of her brother adorns her forearm. It’s an ever-present reminder of the profound pain that’s fueled a fiery mission: to bring change and justice to the Valley.

In 2022, Hernandez ran for the state legislature, upsetting incumbent state Sen. Cesar Chavez in the primary before running unopposed in the general election. For the past two years, the 42-year-old has been a passionate and outspoken advocate of progressive causes, loudly arguing in favor of police and housing reform.

Now, after one term, Hernandez has her sights set on different, more local territory. Instead of running for reelection in the legislature, the progressive firebrand is attempting to hop down to Phoenix City Council, where she can exert influence on the fifth-largest city in the United States.

It’s far from a sure bet. Hernandez is one of four candidates vying for a spot representing District 7, which encompasses much of central and west Phoenix. The others are Martyn Bridgeman, a realtor whose campaign priorities are largely progressive; Michael Nowakowski, a controversial former councilmember with a history of anti-LGBTQ sentiments and corruption allegations; and former state Rep. Marcelino Quiñonez, who resigned to jump into the race after Hernandez announced her candidacy.

Hernandez’s main competition is Quiñonez, who dons dapper suits and sports slicked-back hair. Almost all major figures of Phoenix’s political class have endorsed him, including Mayor Kate Gallego and U.S. Rep. Ruben Gallego. Quiñonez also has the backing of former Vice Mayor Yassamin Ansari, who vacated the District 7 seat to run for Congress, and interim Councilmember Carlos Galindo-Elvira, who was appointed to the body when Ansari left.

Hernandez, who has never cared much about the establishment’s approval, boasts support from the grassroots. Her campaign website touts endorsements from 18 political organizations and labor unions, including Planned Parenthood Advocates of Arizona, Worker Power, the AFL-CIO, Unite Here! Local 11, Young Democrats of Arizona and the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees. Ten organizations and unions have endorsed Quiñonez.

If Hernandez is more of an outsider, that’s good, she says. With so many establishment centrists at the helm, Phoenix City Council needs one.

“I’m still part of this community. I try my best to be out there talking to different folks that are affected by those decisions that happen. I think that is missing in a big way on the council,” Hernandez said. “The majority of the council function within the status quo and aren’t shaking things up, not looking outside the box, not out there talking to the constituency that needs to be talked to: The ones that are struggling to make ends meet.”

Police reform

Earlier this month, Hernandez trekked through the Roosevelt neighborhood on the edge of District 7. As she knocked on door after door, more and more residents told her that only she and Bridgeman had come by to hear their concerns.

Their concerns are also hers, Hernandez says. She’s focused her campaign on a few core topics, including housing and homelessness. Another is at the heart of her own life story: public safety, a term Hernandez says often is misconstrued as more policing and more funding for cops.

“Public safety is so much more than that. It’s safe housing, it’s healthy neighborhoods, it’s can people go use their parks and be safe in their parks?” Hernandez said. “It’s do I have safe child care where my kids can go? Are there after-school programs that are gonna keep our kids off the street?”

It is also policing, of course.

If elected, Hernandez would immediately become the city council’s most outspoken critic of Phoenix’s notoriously violent police force. Since 2014, Phoenix police have killed hundreds of people — including Hernandez’s brother — with countless stories of loss that could have been avoided. In June, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that Phoenix police have a pattern of discriminating by race, using excessive force and trampling the rights of homeless people.

While establishment figures such as Sen. Gallego and Mayor Gallego have been wary of publicly critiquing police, Hernandez has not been shy about doing so. When video surfaced earlier this month of Phoenix cops beating and tasing a deaf Black man in August, Democrats on the council put out mealy-mouthed, we’re-very-concerned statements. In contrast, Hernandez and state Rep. Analise Ortiz released a statement calling the incident “indicative of the larger systemic problems within the Phoenix Police Department.”

In January, Ortiz and Hernandez also teamed up in the legislature to introduce a Family Bill of Rights, which aimed to bring transparency and support to people injured by police and relatives of those killed by law enforcement officers. The bill, which was never heard by the legislature, was informed by Hernandez’s personal experience.

“As we navigated the system in looking for answers and accountability on police violence, we faced endless roadblocks in obtaining police reports, investigative reports, personal belongings of our loved ones and access to resources,” Hernandez said at a press conference introducing the bill.

In a statement provided to New Times, Ortiz called Hernandez “the only candidate who can be trusted to advocate for meaningful transparency, accountability and reform for the Phoenix Police Department.”

While Hernandez is more than willing to call out bad policing, she refutes the notion that she hates cops, with whom she’ll need to have a productive relationship if elected. She said she has engaged with law enforcement for years and doesn’t shy away from those relationships. Her main issue is the fundamental role of the cop in Phoenix and more broadly — though, like many already on the council, she’s not sure if a consent decree with the DOJ is the answer to Phoenix’s issues.

“We’ve become this society that wants to use police to address every single social issue we have. It’s not good for anybody,” Hernandez said. “We have to look at public safety through a different lens. And that’s part of the work, right?”

Housing and homelessness

Policing may be the buzziest issue Phoenix faces, but it’s hardly the only one. While Hernandez knocked doors in downtown Phoenix, the first concern many residents raised was about Phoenix’s twin crises.

“Housing and homelessness come up every day on the doors,” she said.

On the issue of housing, Hernandez has shown the ability to work across the aisle. She was a leader in the Senate on bipartisan solutions for housing problems, sponsoring a bill to legalize the construction of accessory dwelling units — commonly called casitas — to help alleviate the state’s housing shortage.

The bill passed both the House and Senate with bipartisan support before being signed into law by Gov. Katie Hobbs. It was a rare win for those trying to address the housing crisis. “People don’t want to change the status quo to actually bring solutions,” Hernandez said. “So what I was able to lead on these past two years has been huge and unheard of because nobody ever can get that done.”

The bill was opposed by the League of Cities and Towns, including Phoenix, which objected to the fact that the bill allowed casitas to be used as short-term rentals. That clash played out in public earlier this month.

At an Oct. 8 council meeting, Mayor Gallego engaged in a rare, seemingly forced moment of name-dropping. Usually averse to saying anything all that confrontational, Gallego called out Hernandez for her role in passing the bill over the city’s opposition.

“We got some pushback even from Phoenix’s own legislators. For example, state Sen. Anna Hernandez,” Gallego said, going on to read a Hernandez quote about how exclusionary zoning was a bigger issue than allowing casitas to be used as Airbnbs. “It’s just very disappointing.”

In a statement to New Times, Gallego noted that she “often comment(s) on the work of the Arizona Legislature, and how it continuously preempts cities from making common sense decisions.” While she noted she usually directs such comments at Republicans, “in this case it was Senator Hernandez who worked with big developer lobbyists to pass some pretty bad policies.” Gallego added that the city attempted to work with Hernandez on the bill but found little traction.

To Hernandez, the episode was a sign that the city’s priorities are out of whack. She feels Phoenix needs immediate fixes to housing and homelessness, not long-delayed perfect ones.

“We’re never going to find one solution to the housing problem or the homelessness problem,” she said. “But we have to have the political courage to say, ‘Hey, we need to address this, and these are the different steps we can take.’”

One step would address the Valley’s eviction crisis, which was on pace to break records earlier this year. Hernandez wants to create a right-to-counsel program for people who are evicted, something she and her campaign manager, Luke Black, say would cost between $500,000 and $1 million in city funds and would prevent homelessness ahead of time.

That should be a pittance for a city the size of Phoenix, Black said. But, he noted that “the city can’t find that money in a budget where they’re already giving close to $1 billion to the police. There’s a wild disconnect.”

Passing meaningful housing reform — rather than more camping bans that target the city’s sizable unhoused population — would make for an uphill battle. Phoenix’s centrist councilmembers are cozy with landlords, Black claims. Campaign finance records show that in 2023, Phoenix Association of Realtors donated more than $100,000 to the political action committee Invest in Phx, which is run by associates of Mayor Gallego, Ansari and Councilmember Kesha Hodge Washington.

The realtors association also has endorsed Quiñonez.

“One of the ways folks end up homeless is through the rental market. It’s through evictions and predatory landlords,” Black said. “We have to remember that the political establishment is not interested in changing this, which is why we see the landlords endorsing Marcelino. We know that they benefit from the status quo, and they made a move to support the person that would keep the status quo in place.”

Gallego campaign spokesperson Kevin Kirchmeier noted the realtors association contributed to the Phoenix Bond campaign, which will “invest more than $55 million in affordable housing,” including in the district Hernandez is running to represent.

Kirchmeier also criticized Hernandez’s support from the Home Builders Association of Central Arizona, which he claimed prompted her to change her position on Senate Bill 1172, which affected groundwater pumping rights. Hernandez was the lone Democrat to support it and afterward, Kirchmeier said, “the Home Builders Association repaid the favor” and donated $1,000 to Hernandez’s city council campaign. Gov. Katie Hobbs ultimately vetoed the bill.

The Home Builders Association also gave the same amount to councilmembers Ann O’Brien, Jim Waring and J.J. Martinez, who is challenging councilmember Betty Guardado in District 5. Last election cycle, the association donated $1,000 each to Waring and Washington.

When asked about the opposition to her housing plans, Hernandez can only laugh.

“It’s funny because my work on housing has become so much more controversial than my work on policing,” she said. “I guess I wasn’t prepared for that.”

Challenges ahead

If Hernandez wins, though, she better prepare for a fight. She’ll be walking into a lion’s den of pre-existing opposition at City Hall.

The first step is coming out on top Nov. 5, or at least finishing high enough to advance to the run-off election in March. In a crowded field, most of the support seems to be coalescing around Hernandez and Quiñonez.

Both Hernandez and Black suspect Gallego recruited Quiñonez to run because he is unlikely to challenge the status quo. Kirchmeier said Gallego “encouraged” Quiñonez to run, though Quiñonez could not be reached for comment. That echoes a race in 2023, when outspoken, progressive Councilmember Carlos Garcia was unseated by Washington, whom Mayor Gallego endorsed.

New Times was unable to reach Garcia to speak about his experience as one of the council’s progressive voices.

Black said Mayor Gallego’s firm opposition and attack on Hernandez show how determined the mayor is to preserve the status quo.

“This is the mayor’s council. She has built this council over time by strategically recruiting candidates to run in races. The result of that has been, at this point the mayor controls at least five votes,” Black said. “What that has meant for this city is we’re in a housing crisis with no solutions. We’re in an eviction and rent crisis with no solutions. We have a police budget that’s totally out of control with no guardrails.”

Kirchmeier countered that “Phoenix has a very strong council of independent leaders, all of whom have voted differently than the mayor.” He said Gallego led the effort to recruit current councilmember Kevin Robinson but that she “did not recruit any other members of the city council.”

In a much smaller legislative body, it’s true that Hernandez could encounter colder treatment from Gallego and her allies. The shot Gallego took at her over the housing bill was hardly the only time conflict has spilled into the open.

In May 2023, the council voted 5-4 — with Gallego joining its conservative wing in support — to ban public comment, a move that prevented mobile home residents facing imminent eviction from speaking. Hernandez, who was in attendance, rose up in a fury and lambasted the council.

“If you shut them down, I will make it my goal to shut the city down,” Hernandez boomed, pointing her finger at the council.

Perhaps that’s why some who have endorsed Quiñonez have tacitly suggested Hernandez doesn’t play well enough with others to serve on the council. Ansari tended to side with the progressive wing of the council and voted against silencing the mobile home residents. Still, she told the Arizona Republic that she endorsed Quiñonez partly due to his interpersonal skills.

“I think that I trust more in Marcelino’s temperament to deal with some of these challenging issues … without alienating too many other members of the council,” Ansari said.

Ansari declined to comment when reached by New Times. In her statement, Gallego downplayed the effect any discord between her and Hernandez would have on how the council functions. “I have a long record of working with people of all political walks of life,” the statement said, “and I’ll always put aside differences to move Phoenix forward.”

While Galindo-Elvira has also endorsed Quiñonez, he stressed to New Times that he by no means is rebuking Hernandez. “I have nothing against Anna Hernandez,” he said. “When I endorsed Marcelino, I let her know that I would not be campaigning against her or attack her in any way, shape or form.” Galindo-Elvira is also on the ballot for District 7 but only to fill Ansari’s seat for the final four months of her term.

If Mayor Gallego is marshaling her resources to defeat Hernandez, that wouldn’t surprise the state lawmaker. She knows she gets under the mayor’s skin because she doesn’t play by the same rules.

“In politics, we gain political capital that we can use at different times. I’ve saved my political capital to make sure it’s actual things that benefit the community. Not everyone works that way,” Hernandez said. “Sometimes the higher elected officials, when they gain more power, become much more disconnected from the community they serve.”

That’s the message Hernandez is taking to voters with voting already underway. She’ll need to win a seat, and then she’ll need to show she can get things done.

Plenty of progressive goals have been stymied by the city council, which has undercut its own police oversight agency and further criminalized homelessness. Accomplishing meaningful change will require fighting but also give-and-take with councilmembers who aren’t perfectly aligned with Hernandez.

She is undaunted by that challenge. Hernandez worked across the aisle in the Arizona Legislature — with lawmakers much more hostile to progressive ideals than those on the city council — and she feels ready to help steer her city in the same way.

“I know how to work,” Hernandez said, her dark eyes as determined and intense as ever.